Once the toilet is flushed, the contents of its pan are cleansed from the mind, just as they were from the body. They, along with the wet wipes, cotton buds, food scraps and cooking oil are not considered for seconds longer than they are seen. That is until the moment of failure, when the water ceases draining and the pipes block. At this moment all the material washed away without thought becomes present again, irremovable. Sometimes this blockage occurs deeper into the system. Cooking oil from the deep fat fryers of less reputable fast food establishments combines with that from households after being irresponsibly poured down the drain. It begins to congeal within the pipes of the sewer, sticking to its rough sides. The detritus, flushed without thought, acts as scaffold and reinforcement. As the flow of black water slows, more and more becomes stuck in the mass. The system grinds to a halt, the water company is called, and a white plastic suited worker with a poison gas monitor strapped to their side makes a horrifying discovery. There in the dark, they find lurking, a fatberg.

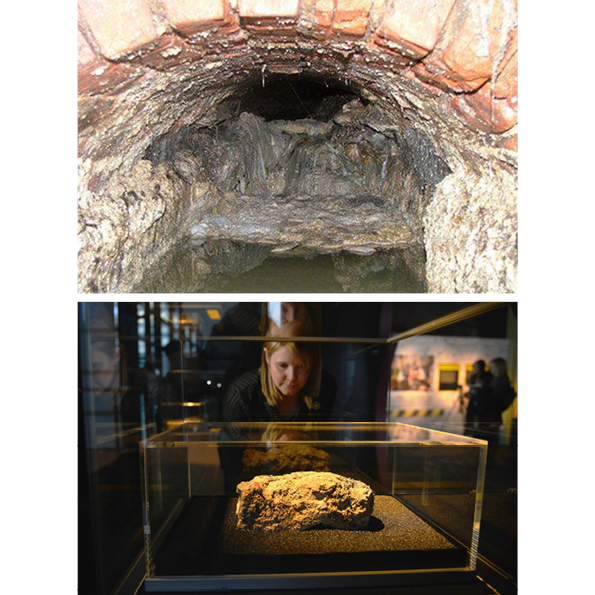

The largest fatberg found in London was 250 m long and weighed 130 tons, it lay beneath the district of Whitechapel. Inside the sewer the fat undergoes a process called saponification, where the fat essentially turns to soap. The resulting fatberg can be concrete hard and due to the confined spaces in which they form must generally be removed by hand. After 9 weeks of work the Whitechapel fatberg was removed. It was mostly turned into biodiesel. However a small section was acquired by the Museum of London and displayed in a glass vitrine. When asked why they had acquired it, curator Vyki Sparkes said “the fatberg is rather like the portrait of Dorian Gray: it shows our disgusting side. Just as in Oscar Wilde’s novel, it is hidden away, getting worse and worse as we pile the accumulated sins of the city into it”

Attempting to combat the problem, many cities now offer food waste collection. The food, including used cooking oil, is then removed and used in a biodigester to create renewable methane gas. For restaurants, companies offer collection. For firms like Munzer Bioindustrie GmbH of Austria they will remove the oil for free. For them the fat has its own value, it is then turned into biodiesel just like the Whitechapel fatberg, but without the costly diversion through the sewer systems. In London, all that remains is a commemorative drain cover reading “The Whitechapel Fatberg was defeated here in 2017”

← Back to Lexicon

The largest fatberg found in London was 250 m long and weighed 130 tons, it lay beneath the district of Whitechapel. Inside the sewer the fat undergoes a process called saponification, where the fat essentially turns to soap. The resulting fatberg can be concrete hard and due to the confined spaces in which they form must generally be removed by hand. After 9 weeks of work the Whitechapel fatberg was removed. It was mostly turned into biodiesel. However a small section was acquired by the Museum of London and displayed in a glass vitrine. When asked why they had acquired it, curator Vyki Sparkes said “the fatberg is rather like the portrait of Dorian Gray: it shows our disgusting side. Just as in Oscar Wilde’s novel, it is hidden away, getting worse and worse as we pile the accumulated sins of the city into it”

Attempting to combat the problem, many cities now offer food waste collection. The food, including used cooking oil, is then removed and used in a biodigester to create renewable methane gas. For restaurants, companies offer collection. For firms like Munzer Bioindustrie GmbH of Austria they will remove the oil for free. For them the fat has its own value, it is then turned into biodiesel just like the Whitechapel fatberg, but without the costly diversion through the sewer systems. In London, all that remains is a commemorative drain cover reading “The Whitechapel Fatberg was defeated here in 2017”

← Back to Lexicon

The Whitechapel Fatberg, in situ and on display.

Sources: Thames Water, Museum of London

Sources: Thames Water, Museum of London