Allegory is a literary device used in numerous forms of art to reveal the hidden meaning of real-world issues and occurrences through a discreet curtain of a symbolic character, place or event.

The allegories of rivers have been in existence since the post-Hellenistic-Age Romans, who personified rivers as mythical figures capable of bringing life and prosperity and at times, capable of wreaking havoc through the power of floods. Romans personified rivers in their artworks as a bull or a man with a bullhead, similar to the Greek myth about the god of rivers- the Achelous, who was defeated by Hercules for the hand of the water nymph Deianeira. Hercules ripped off a horn of Achelous and offered it to Deianeira, who filled it with fruits calling it a 'cornucopia'- another river analogy that turns up repeatedly. Gradually, the rivers became symbolic as bearded reclining men and springs as standing female nymphs throughout the Roman era where long beards, flowing hair with reed crowns, and robes holding urns as origins of the river provided the perception of flowing water. The representation of major rivers - the Tiber, Nile, Euphrates, Tigris, Danube and Rhine - were commonly featured in artworks and coins. The famous painting 'The Four Continents', also known as 'The Four Rivers of Paradise', represents the female personifications of Europe, Asia, Africa and America sitting with the personifications of their respective major rivers – the Danube, the Ganges, the Nile and the Río de la Plata. Vienna's Danube is depicted in the column of Trajan in Rome as a personified male somberly looking over the Roman army as they cross the river. The sculptures in Vienna's water fountains are often personifications of its springs and rivers to celebrate water and its associated technology.

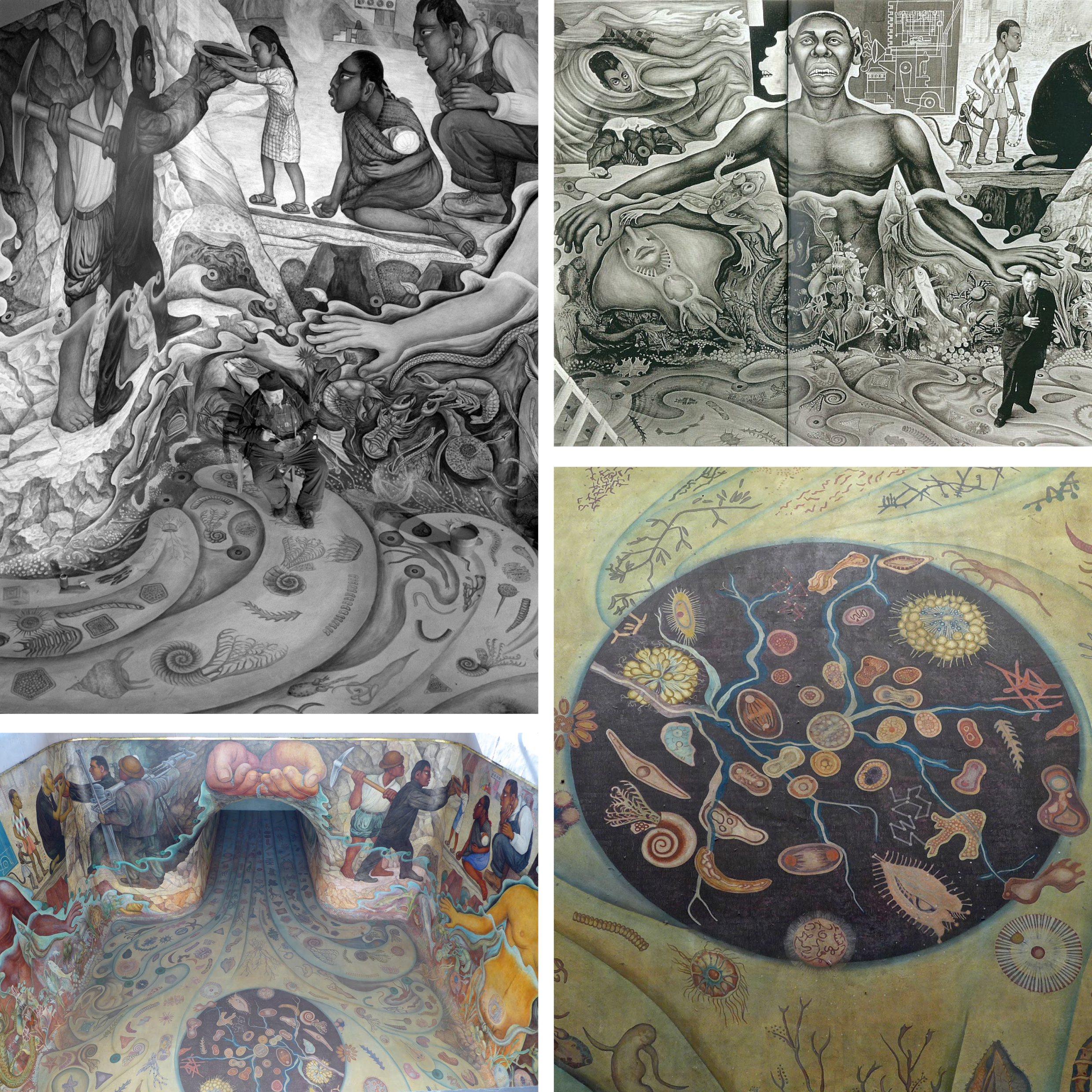

Another allegory of water as an originating element of life on earth and its abiogenesis is observed in 1951, in Rivera's mural of Cárcamo de Dolores. The mural inspired by the theories of Alexander Ivanovich Oparin, a Soviet biochemist, represents the origin of life through various organisms, first men inspired by Olmec art, the importance of workers and technology in providing water to the city, and its importance in daily lives.

← Back to Lexicon

The allegories of rivers have been in existence since the post-Hellenistic-Age Romans, who personified rivers as mythical figures capable of bringing life and prosperity and at times, capable of wreaking havoc through the power of floods. Romans personified rivers in their artworks as a bull or a man with a bullhead, similar to the Greek myth about the god of rivers- the Achelous, who was defeated by Hercules for the hand of the water nymph Deianeira. Hercules ripped off a horn of Achelous and offered it to Deianeira, who filled it with fruits calling it a 'cornucopia'- another river analogy that turns up repeatedly. Gradually, the rivers became symbolic as bearded reclining men and springs as standing female nymphs throughout the Roman era where long beards, flowing hair with reed crowns, and robes holding urns as origins of the river provided the perception of flowing water. The representation of major rivers - the Tiber, Nile, Euphrates, Tigris, Danube and Rhine - were commonly featured in artworks and coins. The famous painting 'The Four Continents', also known as 'The Four Rivers of Paradise', represents the female personifications of Europe, Asia, Africa and America sitting with the personifications of their respective major rivers – the Danube, the Ganges, the Nile and the Río de la Plata. Vienna's Danube is depicted in the column of Trajan in Rome as a personified male somberly looking over the Roman army as they cross the river. The sculptures in Vienna's water fountains are often personifications of its springs and rivers to celebrate water and its associated technology.

Another allegory of water as an originating element of life on earth and its abiogenesis is observed in 1951, in Rivera's mural of Cárcamo de Dolores. The mural inspired by the theories of Alexander Ivanovich Oparin, a Soviet biochemist, represents the origin of life through various organisms, first men inspired by Olmec art, the importance of workers and technology in providing water to the city, and its importance in daily lives.

← Back to Lexicon

Images of Diego Rivera’s mural ‘The Origin of Life’ for Cárcamo de Dolores.

Sources: “Cárcamo de Dolores”, Wikipedia, July 26, 2020, https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/C%C3%A1rcamo_de_Dolores

Sources: “Cárcamo de Dolores”, Wikipedia, July 26, 2020, https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/C%C3%A1rcamo_de_Dolores

- “Rivers of art: Ancient Rome”, River Ecology and Research, September 15, 2016, https://paulhumphriesriverecology.wordpress.com/2016/09/15/rivers-of-art-ancient-rome/

- “The Four Continents”, Wikipedia, March 25, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Four_Continents

- “Departure across the Danube”, Omeka RSS, accessed May 03, 2021, http://omeka.wellesley.edu/piranesi-rome/exhibits/show/column-for-trajan/departure-across-the-danube

-

“Cárcamo de Dolores”, Wikipedia, July 26, 2020, https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/C%C3%A1rcamo_de_Dolores

Legend has it, that -precisely- on May 24, 1065 CE, the Aztecs ventured on an epic migration from their ancestral homeland, Aztlan (“Place of Reeds” or “Place of Egrets”), to the shores of Lake Texcoco, in central Mexico. There, by forming another altépetl, they founded the city of Tenochtitlan, which in time spawned the vast Aztec Empire, famously encountered by Hernan Cortez several hundred years later. The altépetl (plural altepeme) was the local ethnical-political-territorial entity or “city-state” in Mesoamerican societies. The indigenous identity during the Aztec Empire was defined by the altépetl. The word actually combines the Nahuatl word for “water”, ātl, with tepētl, meaning “mountain”, anchoring civilization in a clearly defined territory.1 The Mexican culture and origins are inextricably tied to the elements of earth and water.

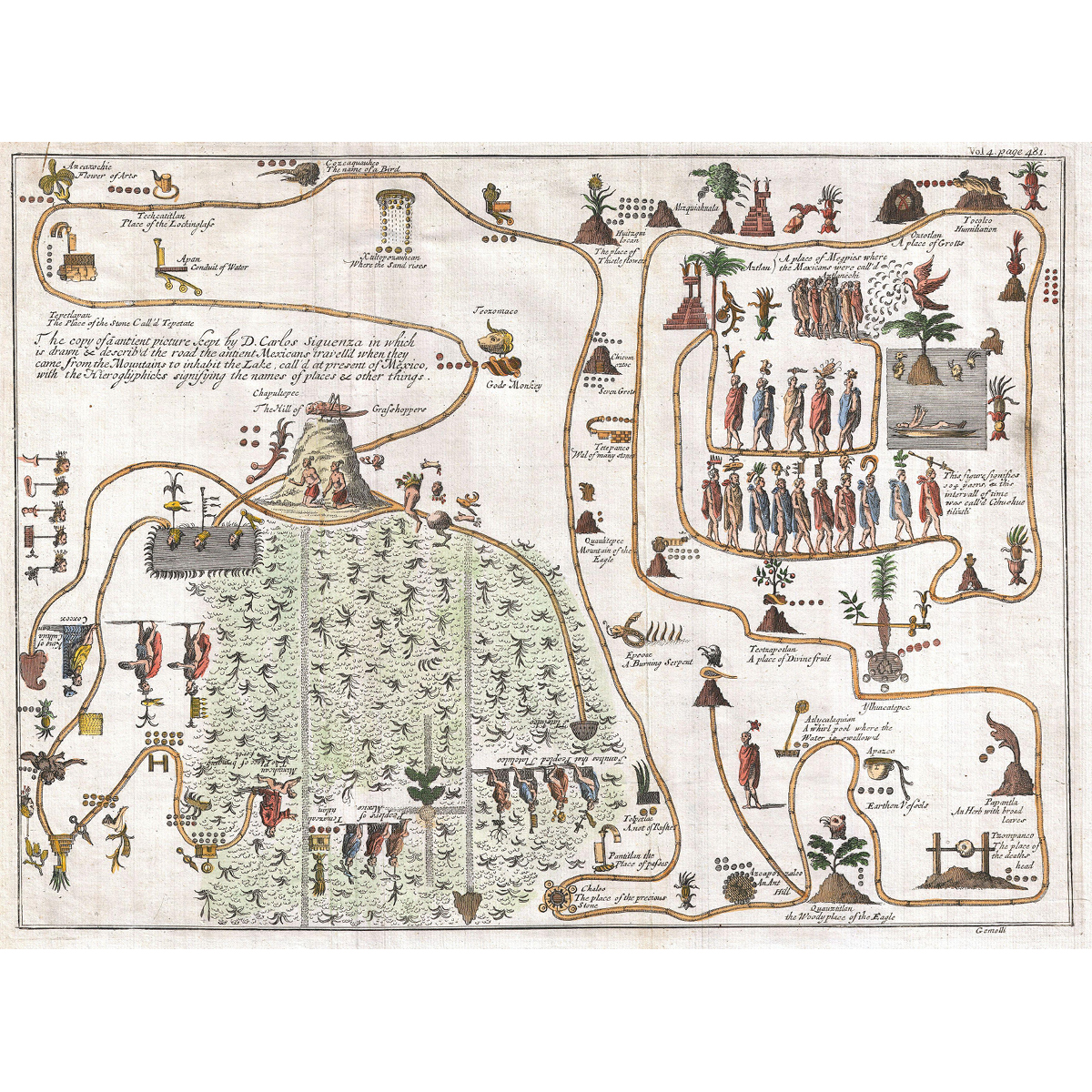

This unusual 1704 map, drawn by Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri, is the first published representation of the legendary Aztec migration from Aztlan, a mysterious paradise somewhere to the northwest of Mexico, to Chapultepec Hill. The road that the ancient Mexicans travelled when they came from the mountain on the lake in order to inhabit Lake Texcoco, is drawn and described with the Hieroglyphics signifying the names of content and places. Aztlan appears here in the upper right corner also as a lake, with a mountain and a palm tree. The progression meanders along many paths and digressions to finally arrive to the upper right quadrant, where we can discern a hill upon which rests a gigantic Grasshopper. This is Chapultepec, known nowadays as Mexico City.2

This unusual 1704 map, drawn by Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri, is the first published representation of the legendary Aztec migration from Aztlan, a mysterious paradise somewhere to the northwest of Mexico, to Chapultepec Hill. The road that the ancient Mexicans travelled when they came from the mountain on the lake in order to inhabit Lake Texcoco, is drawn and described with the Hieroglyphics signifying the names of content and places. Aztlan appears here in the upper right corner also as a lake, with a mountain and a palm tree. The progression meanders along many paths and digressions to finally arrive to the upper right quadrant, where we can discern a hill upon which rests a gigantic Grasshopper. This is Chapultepec, known nowadays as Mexico City.2

Gemelli Map of the Aztec Migration from Aztlan to Chapultepec.

Cárcamo de Dolores, also called del Lerma, is a hydraulic structure located in the Chapultepec Forest of Mexico City. Mexico City receives its fresh water supply from the Cutzamala Distribution System, whose first half of stage I, called the Lerma system, conditioned the water from the Lerma river through channels, pipes, tunnels and storage tanks in 1951. Cárcamo de Dolores, currently part of the Museum of Natural History, was constructed in the same year and is located where the Lerma system’s Atarasquillo - Dos Ríos tunnel, a structure 2.5 meters in diameter, culminates.

The structure was designed by the combined efforts of muralist Diego Rivera, architect Ricardo Rivas and engineer Eduardo Molina as a tribute to water. It was an attempt to integrate public art into a functional building and create a vital concept based on the applications of water in Mexican culture, references to the art of Mesoamerican cultures, and the celebration of technological effort associated with the water distribution system. The building by Rivas is a functionalist building borrowing the form of a classical temple with the roof as a mound and columns on the patio; as well as an abstraction of the elements of the Mesoamerican cultures which are visible in the four gargoyles of the building. Diego Rivera created a mural inside the tunnel, on the four walls and floor of the storage tank where water flows in from the gully. The mural remained underwater for 40 years and was designed considering the effects of water on the mural. The installation of a water fountain outside the building with a sculpture of the god Tlaloc, the god of wind and water, was constructed by Rivera, essentially supposed to be seen from the sky due to its close proximity to the Mexican Airport. The deity has two heads and is built with mosaics and coloured stones. In 2010, along with the restoration of the mural and the fountain, artist Ariel Guzik installed a Lambdoma chamber which is a sound intervention using the technology of sound waves inside the building. The architect Alberto Kalach, in 2010, redesigned the landscape and created a plaza around the building with a capacity of 700 people.

← Back to Lexicon

The structure was designed by the combined efforts of muralist Diego Rivera, architect Ricardo Rivas and engineer Eduardo Molina as a tribute to water. It was an attempt to integrate public art into a functional building and create a vital concept based on the applications of water in Mexican culture, references to the art of Mesoamerican cultures, and the celebration of technological effort associated with the water distribution system. The building by Rivas is a functionalist building borrowing the form of a classical temple with the roof as a mound and columns on the patio; as well as an abstraction of the elements of the Mesoamerican cultures which are visible in the four gargoyles of the building. Diego Rivera created a mural inside the tunnel, on the four walls and floor of the storage tank where water flows in from the gully. The mural remained underwater for 40 years and was designed considering the effects of water on the mural. The installation of a water fountain outside the building with a sculpture of the god Tlaloc, the god of wind and water, was constructed by Rivera, essentially supposed to be seen from the sky due to its close proximity to the Mexican Airport. The deity has two heads and is built with mosaics and coloured stones. In 2010, along with the restoration of the mural and the fountain, artist Ariel Guzik installed a Lambdoma chamber which is a sound intervention using the technology of sound waves inside the building. The architect Alberto Kalach, in 2010, redesigned the landscape and created a plaza around the building with a capacity of 700 people.

← Back to Lexicon

Top view of the hydraulic structure- Cárcamo de Dolores in Mexico City.

Sources: “The Fabulous Underwater Mural of Chapultepec”, Mxcity, accessed May 03, 2021, https://en.mxcity.mx/2016/06/underwater-mural/

Sources: “The Fabulous Underwater Mural of Chapultepec”, Mxcity, accessed May 03, 2021, https://en.mxcity.mx/2016/06/underwater-mural/

Public baths and saunas have been an integral part of the Viennese culture for centuries. The people of Vienna depended on public water for bathing, especially before the invention of indoor plumbing in their homes. Swimming in the Danube was extremely popular amongst the Viennese even before the 15th century; subsequently facing a decline with the ban on public swimming in the river to maintain hygiene with the rise of syphilis and plague.

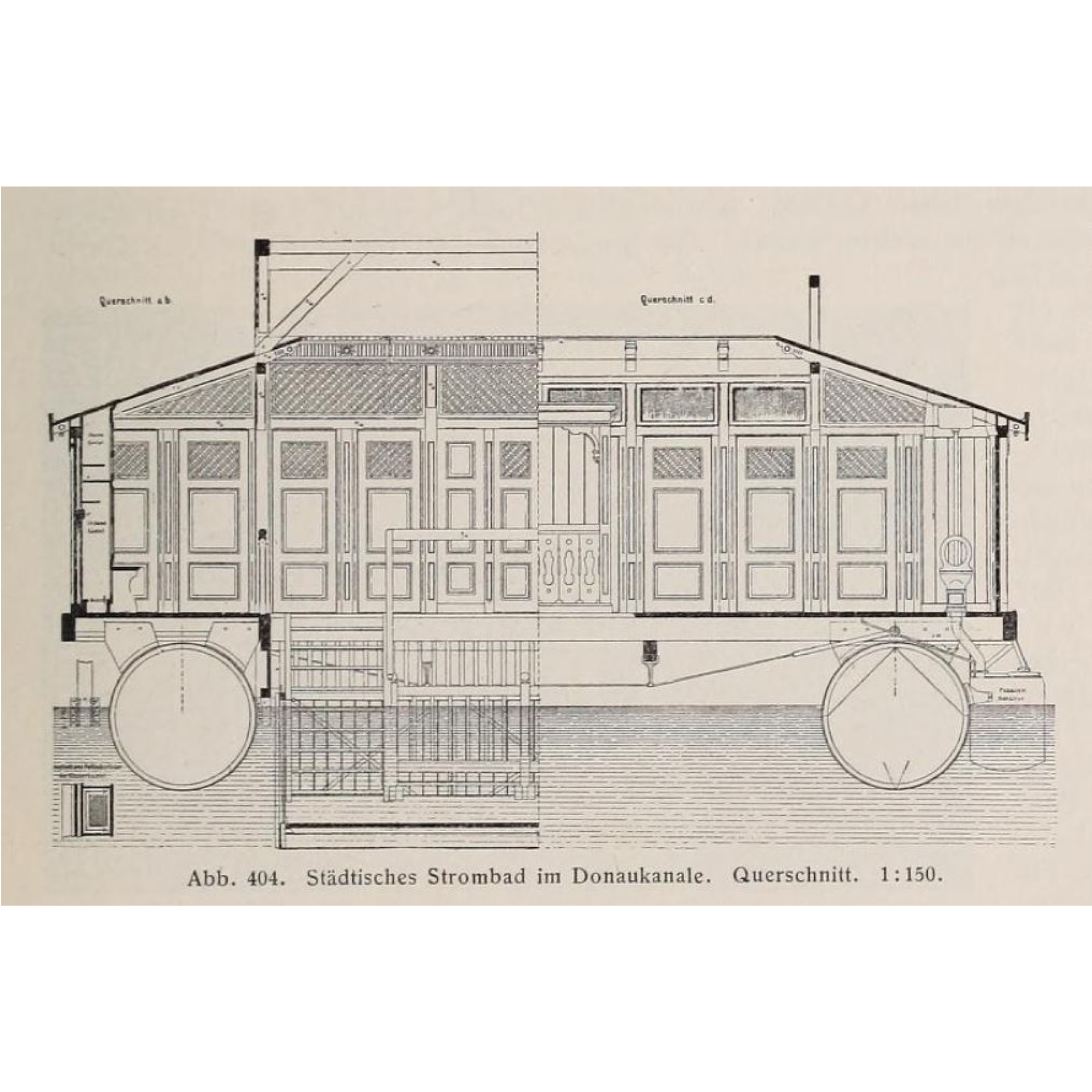

The renewed change in attitudes with the Enlightenment period in the 18th century brought back the tradition of swimming with bathhouses and spas and recognized it as a measure for cleanliness, physical relaxation, and health betterment. The first cold water baths, affordable only to the wealthy, were constructed as floating ships on the Danube to raise physical defences. Soon, Vienna encountered a rise in public baths with free-of-charge baths built by the municipality of Vienna in 1799, the military swimming school in 1813, the first Austrian ladies' swimming school in 1831 before which women had no access to pools; and warm-water urban baths with a capacity of more than 1200 bathers in the Danube-regulation period between 1869-1875. By the mid 19th century, private bathing facilities with heated water similar to the Roman thermal baths were constructed. The Central Bathhouse, constructed in 1889 in the city centre, gained a lot of social reputation and is regarded as the oldest indoor bathing establishment of Vienna. River bathing boat facilities, 60 meters long and 10 meters wide, were constructed on the Danube canal in 1904 following the improvements in the sewage system of Vienna. The Amalienbad, a municipal indoor swimming pool with Art-Deco interiors, was built in 1926 and was "the largest and most modern bathing establishment in Central Europe".

Due to the numerous baths around the Old Danube, Vienna possessed an international reputation as "the city of baths" by the 1920s. However, many historic baths were destroyed during the Second World War. Efforts to rejuvenate them have been made ever since, especially following the implementation of the 1968 public bath concept with 14 pools to be built within a short period of seven years.

← Back to Lexicon

The renewed change in attitudes with the Enlightenment period in the 18th century brought back the tradition of swimming with bathhouses and spas and recognized it as a measure for cleanliness, physical relaxation, and health betterment. The first cold water baths, affordable only to the wealthy, were constructed as floating ships on the Danube to raise physical defences. Soon, Vienna encountered a rise in public baths with free-of-charge baths built by the municipality of Vienna in 1799, the military swimming school in 1813, the first Austrian ladies' swimming school in 1831 before which women had no access to pools; and warm-water urban baths with a capacity of more than 1200 bathers in the Danube-regulation period between 1869-1875. By the mid 19th century, private bathing facilities with heated water similar to the Roman thermal baths were constructed. The Central Bathhouse, constructed in 1889 in the city centre, gained a lot of social reputation and is regarded as the oldest indoor bathing establishment of Vienna. River bathing boat facilities, 60 meters long and 10 meters wide, were constructed on the Danube canal in 1904 following the improvements in the sewage system of Vienna. The Amalienbad, a municipal indoor swimming pool with Art-Deco interiors, was built in 1926 and was "the largest and most modern bathing establishment in Central Europe".

Due to the numerous baths around the Old Danube, Vienna possessed an international reputation as "the city of baths" by the 1920s. However, many historic baths were destroyed during the Second World War. Efforts to rejuvenate them have been made ever since, especially following the implementation of the 1968 public bath concept with 14 pools to be built within a short period of seven years.

← Back to Lexicon

Cross-Section of the Urban river bath in the Danube Canal. Scale 1:15.

Sources: Kortz, Paul, “Vienna at the beginning of the 20th century- A guide in a technical and artistic direction.”, Austrian Association of Engineers and Architects Vienna, Gerlach & Wiedling, 1906. Volume 2, 1905, p. 274, fig. 404, https://archive.org/details/wienamanfangdesx02kort/page/276/mode/2up?view=theater

Sources: Kortz, Paul, “Vienna at the beginning of the 20th century- A guide in a technical and artistic direction.”, Austrian Association of Engineers and Architects Vienna, Gerlach & Wiedling, 1906. Volume 2, 1905, p. 274, fig. 404, https://archive.org/details/wienamanfangdesx02kort/page/276/mode/2up?view=theater

- “Die ehemaligen Bäder am Donaukanal”, Link zur Startseite, accessed May 03, 2021, https://magazin.wienmuseum.at/die-ehemaligen-baeder-am-donaukanal

- “Where the Elites Bathed: Vienna's Central Bath”, Secret Vienna Tours, November 04, 2019, https://secretvienna.org/where-the-elites-bathed-viennas-central-bath/

-

“Central Bathhouse Vienna”, Wikipedia, April 21, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Central_Bathhouse_Vienna

-

“Bäder”, – Wien Geschichte Wiki, accessed May 03, 2021, https://www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/B%C3%A4der

Isolated efforts of conservation and geotourism that develop into joint umbrella organizations like the Association of Austrian Nature Parks and/or work with larger conservation organizations such as the IUCN or UNESCO.

The spring water supply of Vienna comes predominantly from the Styrian Eisenwurzen Nature Park. You can even go to the Wildalpen Spring Water Museum and see the Kläffer spring. Historically, this region was settled in the 11th century and became an iron mining region from the 16th to the 19th century when it transitioned into a tourism focused region. Franz Kraus was an important figure in this transition as he was a very active member in the geological and science field and became a correspondent of the Federal Geological Institute (GBA). As he became more involved in caves and became a speleologist, he brought the Österreichische Touristenklub (OTK) in to collaborate with the caving association he co-founded. Within months he bought a cave and created a tunnel to it, opening it to the public in 1881. By 1883, a small power station was built to make it the first electrically lit cave open to the public and during this the locals decided to make Kraus an honorary member of their community and named it Kraushöhle. After this, Kraus continued to guide the speleology department of the OTK to survey the water conditions in the Carniola region which would go on to influence the melioration projects in the Karst Area.

In 1959, the Österreichisches Wasserrechtsgesetz was passed regulating and defining water. Although nature protections weren’t explicitly mentioned, this policy set precedents by requiring sustainable management especially in regards to water pollution. However, in the Styria region they had already established hunting laws as early as 1947, limiting hunting grounds and species allowed. In the Styria Land Use Planning Law of 1974, conservation and protections for indigenous flora and fauna were established. Then in 1976, the Styrian Nature Conservation Act created 36 Landscape Protection Areas which are not as protected as Nature Parks but are also designated by the state. Soon after, the Styria Mountain and Nature Rescue Service were established in 1977 through local legislation to be in charge of promoting the protection of nature. Most other states did not pass legislation regarding Landscape Protection Areas until the 2000s, after the Nature Parks formed the Verband der Naturparke Österreichs (VNO) in 1995.

← Back to Lexicon

The spring water supply of Vienna comes predominantly from the Styrian Eisenwurzen Nature Park. You can even go to the Wildalpen Spring Water Museum and see the Kläffer spring. Historically, this region was settled in the 11th century and became an iron mining region from the 16th to the 19th century when it transitioned into a tourism focused region. Franz Kraus was an important figure in this transition as he was a very active member in the geological and science field and became a correspondent of the Federal Geological Institute (GBA). As he became more involved in caves and became a speleologist, he brought the Österreichische Touristenklub (OTK) in to collaborate with the caving association he co-founded. Within months he bought a cave and created a tunnel to it, opening it to the public in 1881. By 1883, a small power station was built to make it the first electrically lit cave open to the public and during this the locals decided to make Kraus an honorary member of their community and named it Kraushöhle. After this, Kraus continued to guide the speleology department of the OTK to survey the water conditions in the Carniola region which would go on to influence the melioration projects in the Karst Area.

In 1959, the Österreichisches Wasserrechtsgesetz was passed regulating and defining water. Although nature protections weren’t explicitly mentioned, this policy set precedents by requiring sustainable management especially in regards to water pollution. However, in the Styria region they had already established hunting laws as early as 1947, limiting hunting grounds and species allowed. In the Styria Land Use Planning Law of 1974, conservation and protections for indigenous flora and fauna were established. Then in 1976, the Styrian Nature Conservation Act created 36 Landscape Protection Areas which are not as protected as Nature Parks but are also designated by the state. Soon after, the Styria Mountain and Nature Rescue Service were established in 1977 through local legislation to be in charge of promoting the protection of nature. Most other states did not pass legislation regarding Landscape Protection Areas until the 2000s, after the Nature Parks formed the Verband der Naturparke Österreichs (VNO) in 1995.

← Back to Lexicon

Organizational network adoption and structure originating from Kraushöhle at Steirische Eisenwurzen

Sources: xx

Sources: xx