Vienna was subjected to a growing population by the mid-19th century and required better hygiene and public conveniences with the improved knowledge of diseases. The Vienna City Council founded the Urinal Commission in 1863 to install public toilet facilities throughout the city. Johann Gottlieb Wilhelm Beetz, a German-Austrian building contractor, offered a 25-year contract to the City of Vienna in 1880 to build public toilets modelled on the lavatories of Berlin. There were several protests by the population against building public toilets in the Ringstrasse, resistance by the Schottenstift- a Benedictine monastery, objections from the church authorities which limited the construction in several proposed locations. After several heated discussions and compromises, the proposal got accepted, and the Beetz company built seventy-three facilities in Vienna by 1910, and operated around 200 toilets and urinals till the 1930s.

The first model of toilets, also called Closet-Hauschen, were small wooden houses with cabins for men and women that soon turned out to be lucrative and were described as "practical, quite comfortable and luxuriously furnished". The municipality wanted public toilets to be camouflaged as street furniture, as a result of which, Beetz replaced wood with iron and glass in his design of the public lavatory on the Parkring; fashioning it in a Secessionist style and implementing the form of the waiting halls of the Viennese horse tramway. In 1904, Beetz built the first underground public toilet in Graben based on the architect Franz Krasny's plans in an attempt to make these toilets even more discreet. The underground structure of 14.5 × 7.7 meters with a height of 3 meters is the last existing public Art-Nouveau toilet in Vienna which can be accessed via two staircases with corresponding labels to separate the genders and adorned with two gas lanterns which doubled as ventilation chimneys. Beetz invented the oil siphon in 1883 where the metal urinal in toilets is coated in a special oil containing disinfectant, the 'urinol'. The use of urinol saved water flushing and kept the odours out, creating an early form of the dry urinal for which he received numerous well-deserved honours. In 1903, the City of Vienna decided to switch to these dry urinals to prevent damage in the water flushing systems during winters.

Vienna has always been immersed in art and culture, even in its most banal structures of public toilets built by Wilhelm Beetz listed as monuments, some of which are open for public use even today.

← Back to Lexicon

The first model of toilets, also called Closet-Hauschen, were small wooden houses with cabins for men and women that soon turned out to be lucrative and were described as "practical, quite comfortable and luxuriously furnished". The municipality wanted public toilets to be camouflaged as street furniture, as a result of which, Beetz replaced wood with iron and glass in his design of the public lavatory on the Parkring; fashioning it in a Secessionist style and implementing the form of the waiting halls of the Viennese horse tramway. In 1904, Beetz built the first underground public toilet in Graben based on the architect Franz Krasny's plans in an attempt to make these toilets even more discreet. The underground structure of 14.5 × 7.7 meters with a height of 3 meters is the last existing public Art-Nouveau toilet in Vienna which can be accessed via two staircases with corresponding labels to separate the genders and adorned with two gas lanterns which doubled as ventilation chimneys. Beetz invented the oil siphon in 1883 where the metal urinal in toilets is coated in a special oil containing disinfectant, the 'urinol'. The use of urinol saved water flushing and kept the odours out, creating an early form of the dry urinal for which he received numerous well-deserved honours. In 1903, the City of Vienna decided to switch to these dry urinals to prevent damage in the water flushing systems during winters.

Vienna has always been immersed in art and culture, even in its most banal structures of public toilets built by Wilhelm Beetz listed as monuments, some of which are open for public use even today.

← Back to Lexicon

Drawings of the first underground public toilet in Graben next to the Josefsbrunnen.

Sources: “Öffentliche Bedürfnisanstalt am Graben”, Wikipedia, May 25, 2019, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%96ffentliche_Bed%C3%BCrfnisanstalt_am_Graben

- “Wilhelm Beetz (Bauunternehmer)”, Wikipedia, May 23, 2019, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilhelm_Beetz_(Bauunternehmer)

- “Vienna at Your Convenience: A History of Public Toilets: Archives: The Vienna Review”, Archives | The Vienna Review, accessed May 03, 2021, https://www.theviennareview.at/archives/2012/vienna-at-your-convenience-a-history-of-public-toilets-2

-

“Toilets of Vienna: A Flush of Relief”, Metropole, November 20, 2019, https://metropole.at/toilets-of-vienna-a-flush-of-relief/

In the 19 century most city metropolitans were under social changes that led to significant spatial transformation and modernization involving new technical solutions. Sewer system was a main part of development in city sanitation, that was an urgent issue to be solved to overcome cholera. In Vienna under the pressure of the Revolution of 1848 and economic growth 1850 it was decided to free areas of the military fortification for public use. The project of Ringstrasse consisted of streets, boulevards, new public buildings and institutions. While the famous and outstanding projects of Sitte and Wagner, there was another side of city development that are underground systems, invisible part of the same ambition. The sewer network already existed by this time in the old center but it became a coordinated and organized system only in 1850. During Ringstrasse building there was a sewer construction boom in 1861. New improvement works were implemented that was sewer collectors building in the suburbs in 1861 and covering the River Wien in Wien Canal in 1898.

The Third Man movie shows this invisible underground layer of Vienna. The criminal, Lime, uses the underground sewage system to move between sectors unwitnessed during the occupation of Vienna. He also tries to escape from police by going down in the labyrinth of sewer tunnels. The police work both searching inside the underground system and guarding outside at sewage hatches that exposed connections of the underground system with the real city and alternative links between city sites.1

Through 19 century modernisation, afterwar repairment and last digital improvements Vienna’s sewer system represents a 2,400 km wide net of canals and pipes, dropping and removing about 15 tonnes of deposits per day.2

← Back to Lexicon

Scenes of “The Third Man”

Sources: “The Third Man”movie, Carol Reed, 1949.

Sources: “The Third Man”movie, Carol Reed, 1949.

- “The Third Man”movie, Carol Reed, 1949.

- https://www.wien.gv.at/english/environment/sewer-system/

The first hour of rain in big cities is more polluting than fecal water.1 Rainfall drags contamination which ends up into sewers, rivers and seas. To prevent it, storm tanks not only remove polluted solids from the rainfall before it is redirected to the cycle, but they also absorb surplus water to avoid sewerage collapse, river overflow and city flooding. They function as a sewerage infrastructure consisting of a deposit dedicated to capture and retain the rainwater transported by collectors. They come into action when there is very intense rainfall and the drainage capacity of the water is lower than the volume of rain.

Madrid and Tokyo have the largest storm drainage systems in the world. Composed of a grid of oversized pillars cast from tons of reinforced concrete, these underground temples work as latent spaces waiting for the rain to come. While Tokyo’s storm tank is made up of a network of five silos connected by four miles of tunnels and Madrid’s tank is a large rectangular deposit hidden under a golf park, Mexico City has a different system. Contrary to the gigantic underground temples which function under a centralized management, rain water in Mexico City is managed by decentralized citizen initiatives such as “Isla Urbana”. They develop rainwater harvesting projects focused on the high areas to the South of Mexico City, where the largest number of homes don’t have connection to the drinking water.2

The dichotomies between superficial and underground, viewed and hidden, centralized and decentralized are blurred. Independently of their differences, these two systems respect the same cycle, being understood as actants3 with which the city negotiates its survival.

Christoffer-Rudquist. Japan’s Storm Tank

Sources: https://www.wired.com/2017/04/christoffer-rudquist-tokyo-drainage-system/

Sources: https://www.wired.com/2017/04/christoffer-rudquist-tokyo-drainage-system/

- The first hour of rain in big cities, https://www.lasexta.com

-

Isla Urbana, https://islaurbana.org/

-

Bruno Latour, Paris Ville Invisible, 1998

30 - 103 AD

Roman hydraulic engineer, politician and author of technical treatises

Sextus Julius Frontinus was appointed the title “Curator Aquarum”, a position in Ancient Rome in order to administer the aqueduct system. He can be referred to as he Vitruvius of the plumbers, since he is the author of the first known technical treatise. He wrote De aquaeductu urbis Romae, a milestone in two volumes on Roman aqueducts providing valuable information, the first official report of an investigation about engineering works ever to have been published.

Below is an example of his description on Ajutage quinaria, a tube through which water is discharged; an efflux tube; as, the ajutage of a fountain.

“Those who refer it to Vitruvius and the plumbers, declare that it was so named from the fact that a flat sheet of lead 5 digits wide, made up into a round pipe, forms this ajutage. But this is indefinite, because the plate, when made up into a round shape, will be extended on the exterior surface and contracted on the interior surface. The most probable explanation is that the quinaria received its name from having a diameter of 5⁄4 of a digit, a standard which holds in the following ajutages also up to the 20‑pipe, the diameter of each pipe increasing by the addition of ¼ of a digit. For example the 6‑pipe is six quarters in diameter, a 7‑pipe seven quarters, and so on by a uniform increase up to a 20‑pipe.”1

← Back to Lexicon

Roman Aqueduct index of sections. Drawings by Ioannis Poleni.

Sources: https://www.dmg-lib.org/dmglib/streambook/index.jsp?bookid=23059009

Allegory is a literary device used in numerous forms of art to reveal the hidden meaning of real-world issues and occurrences through a discreet curtain of a symbolic character, place or event.

The allegories of rivers have been in existence since the post-Hellenistic-Age Romans, who personified rivers as mythical figures capable of bringing life and prosperity and at times, capable of wreaking havoc through the power of floods. Romans personified rivers in their artworks as a bull or a man with a bullhead, similar to the Greek myth about the god of rivers- the Achelous, who was defeated by Hercules for the hand of the water nymph Deianeira. Hercules ripped off a horn of Achelous and offered it to Deianeira, who filled it with fruits calling it a 'cornucopia'- another river analogy that turns up repeatedly. Gradually, the rivers became symbolic as bearded reclining men and springs as standing female nymphs throughout the Roman era where long beards, flowing hair with reed crowns, and robes holding urns as origins of the river provided the perception of flowing water. The representation of major rivers - the Tiber, Nile, Euphrates, Tigris, Danube and Rhine - were commonly featured in artworks and coins. The famous painting 'The Four Continents', also known as 'The Four Rivers of Paradise', represents the female personifications of Europe, Asia, Africa and America sitting with the personifications of their respective major rivers – the Danube, the Ganges, the Nile and the Río de la Plata. Vienna's Danube is depicted in the column of Trajan in Rome as a personified male somberly looking over the Roman army as they cross the river. The sculptures in Vienna's water fountains are often personifications of its springs and rivers to celebrate water and its associated technology.

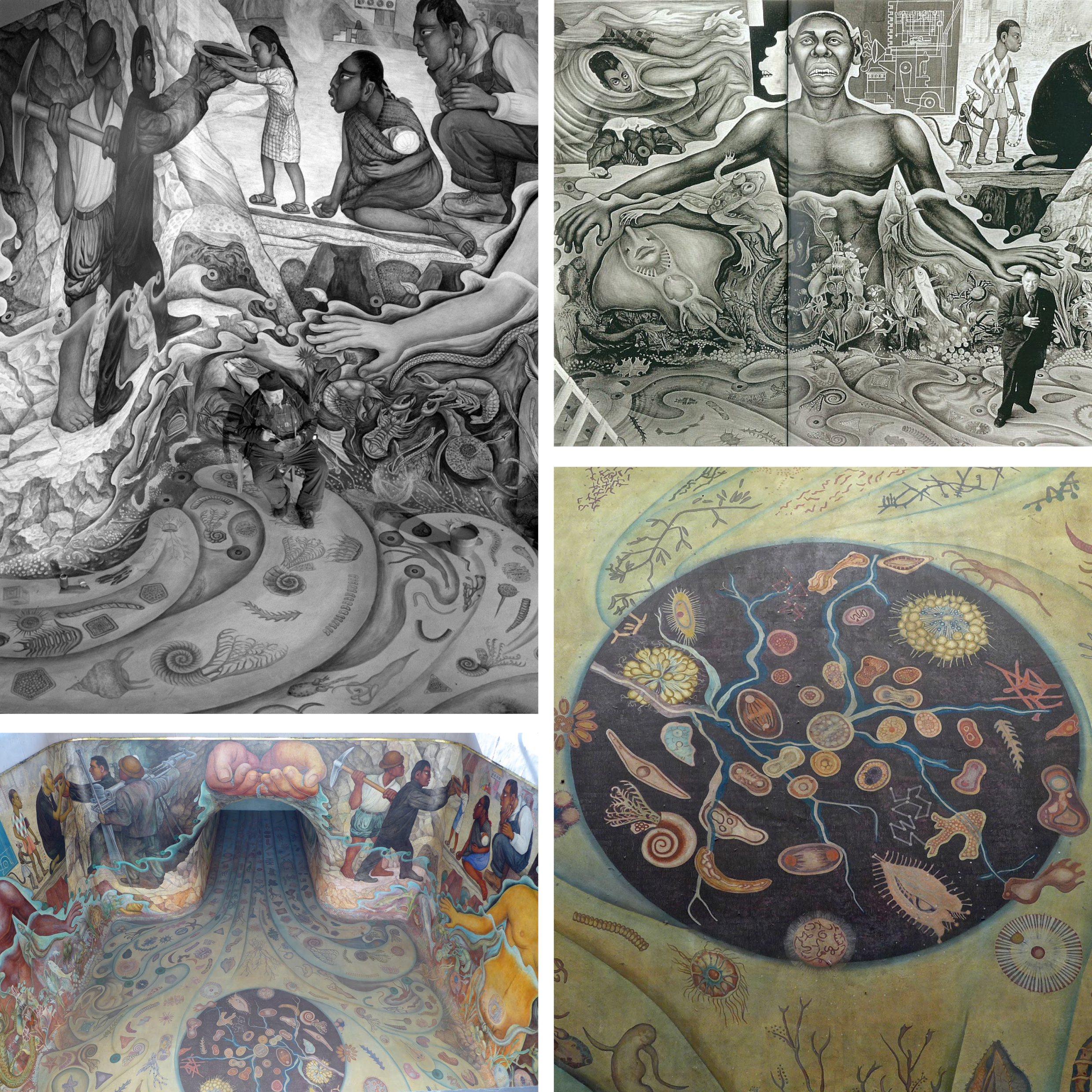

Another allegory of water as an originating element of life on earth and its abiogenesis is observed in 1951, in Rivera's mural of Cárcamo de Dolores. The mural inspired by the theories of Alexander Ivanovich Oparin, a Soviet biochemist, represents the origin of life through various organisms, first men inspired by Olmec art, the importance of workers and technology in providing water to the city, and its importance in daily lives.

← Back to Lexicon

The allegories of rivers have been in existence since the post-Hellenistic-Age Romans, who personified rivers as mythical figures capable of bringing life and prosperity and at times, capable of wreaking havoc through the power of floods. Romans personified rivers in their artworks as a bull or a man with a bullhead, similar to the Greek myth about the god of rivers- the Achelous, who was defeated by Hercules for the hand of the water nymph Deianeira. Hercules ripped off a horn of Achelous and offered it to Deianeira, who filled it with fruits calling it a 'cornucopia'- another river analogy that turns up repeatedly. Gradually, the rivers became symbolic as bearded reclining men and springs as standing female nymphs throughout the Roman era where long beards, flowing hair with reed crowns, and robes holding urns as origins of the river provided the perception of flowing water. The representation of major rivers - the Tiber, Nile, Euphrates, Tigris, Danube and Rhine - were commonly featured in artworks and coins. The famous painting 'The Four Continents', also known as 'The Four Rivers of Paradise', represents the female personifications of Europe, Asia, Africa and America sitting with the personifications of their respective major rivers – the Danube, the Ganges, the Nile and the Río de la Plata. Vienna's Danube is depicted in the column of Trajan in Rome as a personified male somberly looking over the Roman army as they cross the river. The sculptures in Vienna's water fountains are often personifications of its springs and rivers to celebrate water and its associated technology.

Another allegory of water as an originating element of life on earth and its abiogenesis is observed in 1951, in Rivera's mural of Cárcamo de Dolores. The mural inspired by the theories of Alexander Ivanovich Oparin, a Soviet biochemist, represents the origin of life through various organisms, first men inspired by Olmec art, the importance of workers and technology in providing water to the city, and its importance in daily lives.

← Back to Lexicon

Images of Diego Rivera’s mural ‘The Origin of Life’ for Cárcamo de Dolores.

Sources: “Cárcamo de Dolores”, Wikipedia, July 26, 2020, https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/C%C3%A1rcamo_de_Dolores

Sources: “Cárcamo de Dolores”, Wikipedia, July 26, 2020, https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/C%C3%A1rcamo_de_Dolores

- “Rivers of art: Ancient Rome”, River Ecology and Research, September 15, 2016, https://paulhumphriesriverecology.wordpress.com/2016/09/15/rivers-of-art-ancient-rome/

- “The Four Continents”, Wikipedia, March 25, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Four_Continents

- “Departure across the Danube”, Omeka RSS, accessed May 03, 2021, http://omeka.wellesley.edu/piranesi-rome/exhibits/show/column-for-trajan/departure-across-the-danube

-

“Cárcamo de Dolores”, Wikipedia, July 26, 2020, https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/C%C3%A1rcamo_de_Dolores