Lake Texcoco was a natural lake within the “Anahuac” or the Valley of Mexico. An indicator of human presence throughout history, the most prominent of the Mexican civilizations were formed around Lake Texcoco. It is believed that the lake disappeared and re-formed at least 10 times in the last 30,000 years.1 In order to control flooding, most of the lake was drained by the Spanish in the 17th century.

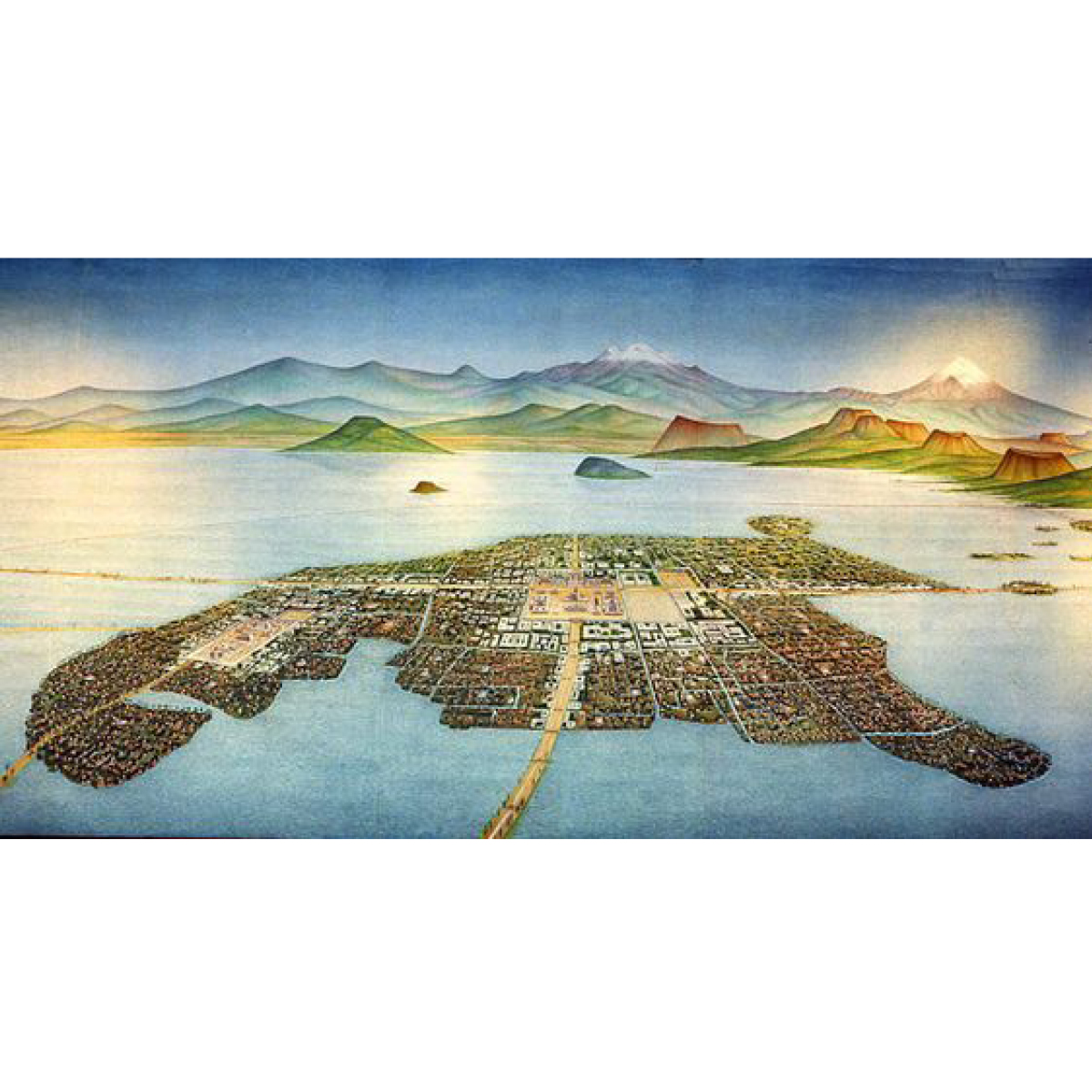

Tenochtitlán, in the heart of what is now Mexico City, was the largest altépetl and capital of the Aztec Empire. It was located on an artificial island in the middle of Lake Texcoco, a strange place for any capital, ancient or modern. On the outskirts of the lake stands an even older cultural complex, the ancient civilization of Teotihuacan, known for the most architecturally significant Mesoamerican. The later Aztecs of Tenochtitlán saw these magnificent ruins and claimed a common ancestry with the Teotihuacanos, modifying and adopting aspects of their culture.2

Nowadays, the area along with the Aztec’s massive canal systems are long drained. The only remnants of ancient Lake Texcoco have turned into a major tourist attraction around the area of Xochimilco, showcasing -among others- the ancient Mexican version of a polder system, through a network of flower-perfumed canals. The traditional chinampas (floating gardens) that once fed the great nation are smaller, but still here; the brightly painted trajineras (flat-bottomed boats) may now come equipped with engines, but they are still festively decorated, and many carry troupes of mariachis and offer relaxed "restaurant" service.3

Despite the drainage issues, water is still present around Lake Texcoco, bringing ancient cultures into life as the civilization of Teotihuacan is constantly revealed due to soil erosion by the high tides. Mexico City is a contemporary paradox: sinking and running out of water simultaneously. At the same time, the ancient lake is reclaiming parts of the scrapped airport in the greater region of Mexico City, leading the dream of restoring the landscape to its former glory.

← Back to Lexicon

Tenochtitlán, in the heart of what is now Mexico City, was the largest altépetl and capital of the Aztec Empire. It was located on an artificial island in the middle of Lake Texcoco, a strange place for any capital, ancient or modern. On the outskirts of the lake stands an even older cultural complex, the ancient civilization of Teotihuacan, known for the most architecturally significant Mesoamerican. The later Aztecs of Tenochtitlán saw these magnificent ruins and claimed a common ancestry with the Teotihuacanos, modifying and adopting aspects of their culture.2

Nowadays, the area along with the Aztec’s massive canal systems are long drained. The only remnants of ancient Lake Texcoco have turned into a major tourist attraction around the area of Xochimilco, showcasing -among others- the ancient Mexican version of a polder system, through a network of flower-perfumed canals. The traditional chinampas (floating gardens) that once fed the great nation are smaller, but still here; the brightly painted trajineras (flat-bottomed boats) may now come equipped with engines, but they are still festively decorated, and many carry troupes of mariachis and offer relaxed "restaurant" service.3

Despite the drainage issues, water is still present around Lake Texcoco, bringing ancient cultures into life as the civilization of Teotihuacan is constantly revealed due to soil erosion by the high tides. Mexico City is a contemporary paradox: sinking and running out of water simultaneously. At the same time, the ancient lake is reclaiming parts of the scrapped airport in the greater region of Mexico City, leading the dream of restoring the landscape to its former glory.

← Back to Lexicon

Tenochtitlan, City of Aztecs in Ancient Mexico, in the middle of lake Texcoco.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lake_Texcoco

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Teotihuacan

-

https://www.viator.com/Mexico-City/d628

Caracol Ecatepec was built in 1942 by SOSA Texcoco to desalinate the water of Lake Texcoco. Designed by Nabor Carrillo, the retention basin and a desalination plant were located over the drained site of Lake Texcoco.1 The 3,200m in diameter basin was called “the snail” from its short spiral-shaped concrete levee that circles it.1 The water from the lake entered from a pump house on an island in the middle of the basin and was channeled outward and clockwise.1 The channel increases in width while decreases in depth until it becomes too shallow to flow further.1 The water evaporates in the opposite direction.1 This allowed for a predictable collection of 100 tons of salts per day.1 The desalinated water that was extracted was used by the factories nearby.

A lack of understanding of the actual process caused the process to be more expensive than expected. In 1967, Lake Texcoco was further exploited by discovering and cultivating its blue algae. The algae are collected by screens and processed into dry nutritional supplement powder for commercial sale branded "Spirulina Mexicana". In December 1986, SOSA Texcoco went bankrupt from a series of strikes and the slow hand labor forced by its snail shape. In 1991, the company and facilities were sold at a low rate to a collective of investors called Sociedad Anónima de Capital Variable. Sociedad Anónima de Capital Variable tried to negotiate the collective bargaining contracts for manual laborers that were mandated upon SOSA Texcoco by the Madrid administration. In 1991, the Mexican Supreme Court ruled that the old contracts must be honored if any profit-seeking business were to resume operations. This forced Sociedad Anónima de Capital Variableto to fold. The government then liquidated the original deed, voided the worker contracts, and seized the inactive facility as a public asset.

In 2000, Caracol was redeveloped with 13,000 new units of low-income housing and a shopping mall. With the additional development and the informal growing settlement of El Salado nearby, the basin cannot expand.The basin is currently owned by the Mexican government and in use as a reservoir for industrial facilities within Mexico City. It is filled from a junction with the Canal de Sal that runs along the south edge of the facility and connects it to the rest of the Mexico City drainage basin.

← Back to Lexicon

A lack of understanding of the actual process caused the process to be more expensive than expected. In 1967, Lake Texcoco was further exploited by discovering and cultivating its blue algae. The algae are collected by screens and processed into dry nutritional supplement powder for commercial sale branded "Spirulina Mexicana". In December 1986, SOSA Texcoco went bankrupt from a series of strikes and the slow hand labor forced by its snail shape. In 1991, the company and facilities were sold at a low rate to a collective of investors called Sociedad Anónima de Capital Variable. Sociedad Anónima de Capital Variable tried to negotiate the collective bargaining contracts for manual laborers that were mandated upon SOSA Texcoco by the Madrid administration. In 1991, the Mexican Supreme Court ruled that the old contracts must be honored if any profit-seeking business were to resume operations. This forced Sociedad Anónima de Capital Variableto to fold. The government then liquidated the original deed, voided the worker contracts, and seized the inactive facility as a public asset.

In 2000, Caracol was redeveloped with 13,000 new units of low-income housing and a shopping mall. With the additional development and the informal growing settlement of El Salado nearby, the basin cannot expand.The basin is currently owned by the Mexican government and in use as a reservoir for industrial facilities within Mexico City. It is filled from a junction with the Canal de Sal that runs along the south edge of the facility and connects it to the rest of the Mexico City drainage basin.

← Back to Lexicon

El Caracol in mid-20th century.

Sources: Imen Hamed, “The Evolution and Versatility of Microalgal Biotechnology: A Review,” Wiley Online Library (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, September 26, 2016), https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1541-4337.12227.

Sources: Imen Hamed, “The Evolution and Versatility of Microalgal Biotechnology: A Review,” Wiley Online Library (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, September 26, 2016), https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1541-4337.12227.

- Jose Castillo, “Peripheral Landscapes, El Caracol, Mexico City,” Architectural Design 78, no. 1 (2008): pp. 64-67, https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.611.

-

“El Caracol, Ecatepec,” Wikipedia (Wikimedia Foundation, April 10, 2020), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/El_Caracol,_Ecatepec.