Nagakin Capsule Tower

Idealization of a system, High-Tech, Recycle, Building, Housing, Construction, Infrastructure, Drawing

The Nakagin Capsule still stands today in the neighbourhood of Giza. In oblivion, the soon to be demolished building awaits its destiny. The first of his class, capsules were a recurrent theme in Metabolism, an architectural movement of the late 50s in Japan. A post-war opportunity to change, where theoretical and tangible projects were created based on the reshaping of the new city. Thanks to a handful of visionaries, japan rapidly transitioned from a defeated country to a country in constant reconstruction. The city was now a living organism that could grow and change, often composed of a main structure that would allow these modifications and flexible capsule units to inhabit. As a result of the war, the limits of space took their minds to the sky and the sea with projects such as Arata Isozaki’s City in the Air and Kenzo Tange’s Tokyo Bay.1

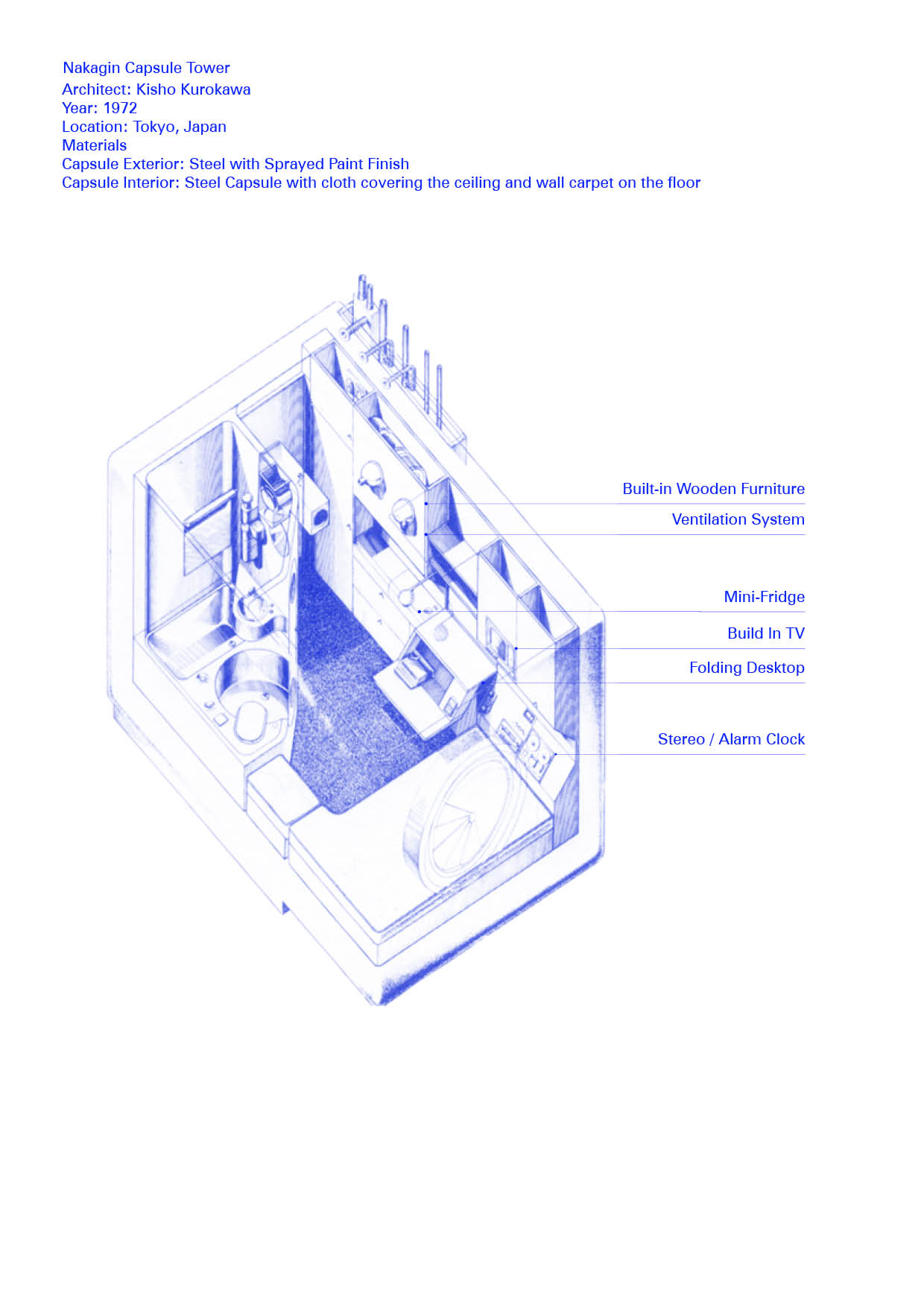

The Capsule was the new typology, a standardization of a prototype that with the technology at hand could be prefabricated and placed into a fixed structure, it not only proposed new ways of building, but also new ways of domesticity. The Nakagin Capsule Tower of 1972 by Architect Kisho Kurokawa, has a cubic design that could be extended by attaching some units together, although the main unit includes a small bathroom and a common area with the bed beside the circular window. Its interior is compound by prefabricated fixed wooden furniture and installed appliances or commodities. These small units were the result of the growing population moving to the suburbs, the Capsule Tower was meant to be a studio or residence with a brief stay for working people that had to crash for the night in Tokyo.2

Comparable to the spirit of the capsule and its minimal dimensions. Charlotte Perriand’s Mountain cabins were also prefabricated and of easy assemblance in situ, with modular interiors and isolated units such as the Bivouac Cabin and the Tunneu Shelter, which resemblance to Kenji Ekuan Pumpkin House is uncanny.[3] These projects fulfil the needs of the inhabitant in a frugal manner while proposing new ways of temporary inhabitation.

1. Rem Koolhaas and Hans Ulrich Obrist, “Project Japan: Metabolism Talks…”, Taschen, 2011.

2. Fala, “Kisho Kurokawa Architect and Associates, Nakagin Casule Tower, 1972”, Divisare, 2008.

3. Jayme DB, charlotte perriand + pierre jeanneret: le refuge tonneau, DesignBoom.com, 2011.

Idealization of a system, High-Tech, Recycle, Building, Housing, Construction, Infrastructure, Drawing

The Nakagin Capsule still stands today in the neighbourhood of Giza. In oblivion, the soon to be demolished building awaits its destiny. The first of his class, capsules were a recurrent theme in Metabolism, an architectural movement of the late 50s in Japan. A post-war opportunity to change, where theoretical and tangible projects were created based on the reshaping of the new city. Thanks to a handful of visionaries, japan rapidly transitioned from a defeated country to a country in constant reconstruction. The city was now a living organism that could grow and change, often composed of a main structure that would allow these modifications and flexible capsule units to inhabit. As a result of the war, the limits of space took their minds to the sky and the sea with projects such as Arata Isozaki’s City in the Air and Kenzo Tange’s Tokyo Bay.1

The Capsule was the new typology, a standardization of a prototype that with the technology at hand could be prefabricated and placed into a fixed structure, it not only proposed new ways of building, but also new ways of domesticity. The Nakagin Capsule Tower of 1972 by Architect Kisho Kurokawa, has a cubic design that could be extended by attaching some units together, although the main unit includes a small bathroom and a common area with the bed beside the circular window. Its interior is compound by prefabricated fixed wooden furniture and installed appliances or commodities. These small units were the result of the growing population moving to the suburbs, the Capsule Tower was meant to be a studio or residence with a brief stay for working people that had to crash for the night in Tokyo.2

Comparable to the spirit of the capsule and its minimal dimensions. Charlotte Perriand’s Mountain cabins were also prefabricated and of easy assemblance in situ, with modular interiors and isolated units such as the Bivouac Cabin and the Tunneu Shelter, which resemblance to Kenji Ekuan Pumpkin House is uncanny.[3] These projects fulfil the needs of the inhabitant in a frugal manner while proposing new ways of temporary inhabitation.

1. Rem Koolhaas and Hans Ulrich Obrist, “Project Japan: Metabolism Talks…”, Taschen, 2011.

2. Fala, “Kisho Kurokawa Architect and Associates, Nakagin Casule Tower, 1972”, Divisare, 2008.

3. Jayme DB, charlotte perriand + pierre jeanneret: le refuge tonneau, DesignBoom.com, 2011.