“Fire the shoe clerk!”

Concrete Object, Fashion, Light, Consumption, Building, Ginza, Real Estate, Economy, Lifestyle, Diagram

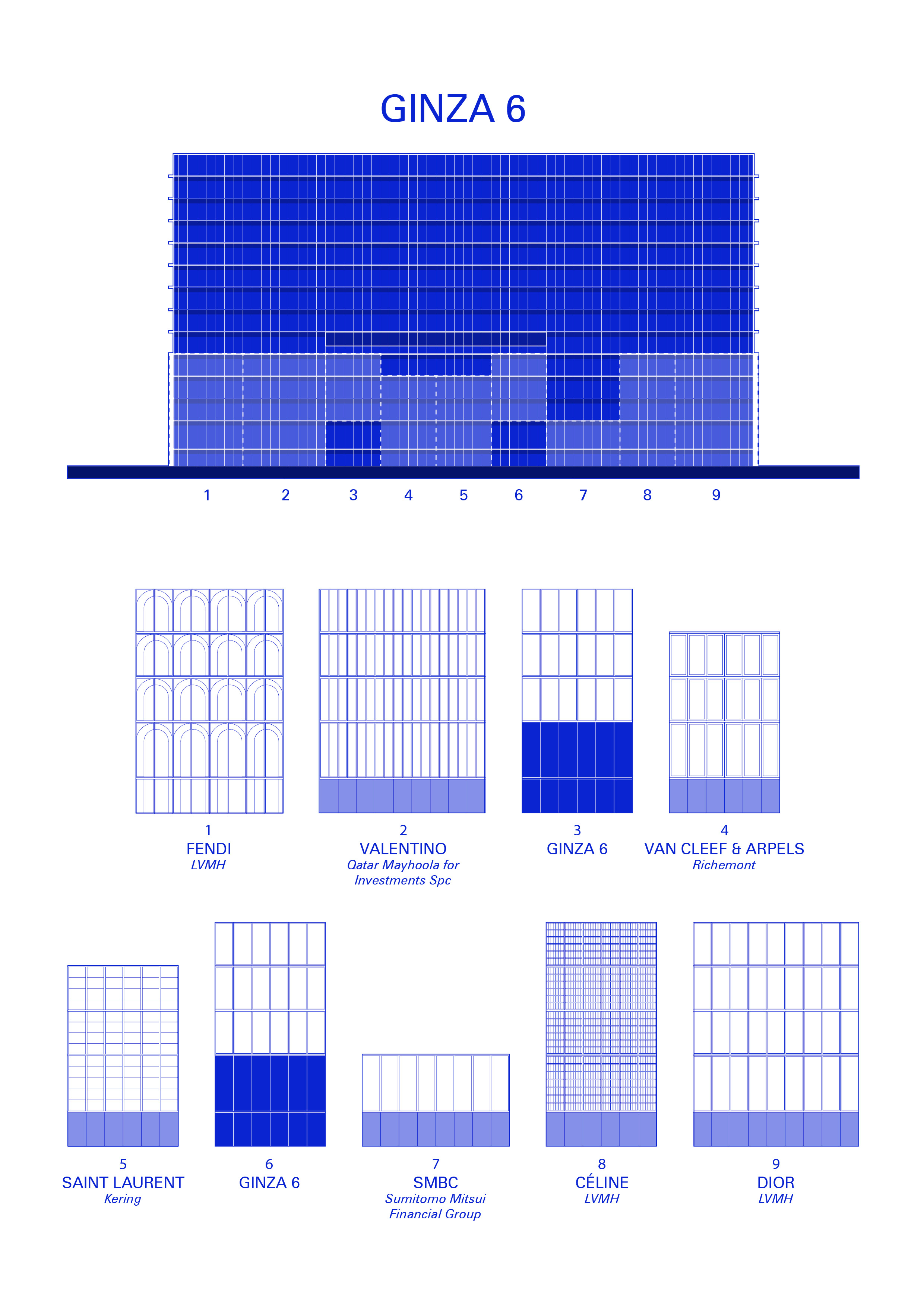

Louis Vuitton and Moët Hennessy merged in 1987, to create the world’s largest conglomerate specializing in luxury goods. In the years that followed, brands like Givenchy (1988), Céline (1996), and Marc Jacobs (1997) were acquired, indicating a big change in the global fashion industry.1 In the same period, Japan consolidated itself as a key player in the luxury market, at a time when property in Tokyo was relatively affordable post-bubble-burst. Kih Kotoyama pinpoints this moment with the acquisition of land, and consequent construction of flagship stores, by Hermès, Louis Vuitton, and Prada, at the turn of the millennium. The multi-billion yen investments these developments required, were recouped not by direct sales, but rather by the advertising potential of these buildings. They were effectively billboards, and the brightly lit facades were designed as such. “The building’s interior is of little concern,” Kotoyama writes, “because it’s recognition in the area as an icon is essential.”2

Similar tactics are now employed by fashion brands in countless shops around Ginza and Aoyama. None of these are bigger than Ginza Six: a 47,000m2 luxury shopping mall. A considerable part of the eighty-six billion yen investment was done by LVMH, and ten of the original tenants were Maisons from the group.3 Three of these – Fendi, Céline, and Dior – open themselves up to Chuo Dori Avenue, collectively forming a portfolio of sorts for the French conglomerate. Their facades, lampion-like structures that light up at night, are placed in front of the non-descript skeleton that forms the mall. The disconnect between exterior and interior, as brought forward by Kotoyama, returns in powerful fashion, and highlights the latest developments in the global fashion economy. Notably, Ginza Six is yet another iteration of Matsuzakaya, the historic department store that has changed the way the Japanese shop in this very location. It adapted a Western way of shopping early in the twentieth century, and became the very first store to allow shoes being worn everywhere inside.4

1. LVMH, “Milestones,” LVMH.com. Accessed March 8, 2020. https://www.lvmh.com/group/milestones-lvmh/1593-to-the-present/ 2. Koh Kitayama, Yoshiharu Tuskamoto, et al., Tokyo Metabolizing, (Tokyo: Toto, 2010), 15-17.

3. LVMH, “Ten LVMH Maisons open in Ginza Six retail complex in Tokyo,” LVMH.com, April 18, 2017. Accessed March 8, 2020. https://www.lvmh.com/news-documents/news/ten-lvmh-maisons-open-in-ginza-six-retail-complex-in-tokyo/

4. The Japan Times, “Matsuzakaya closes Ginza flagship for high-rise makeover,” The Japan Times, July 1, 2013. Accessed March 8, 2020. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2013/07/01/business/corporate-business/matsuzakaya-closes-ginza-flagship-for-high-rise-makeover/

See photos: Ginza Six

Concrete Object, Fashion, Light, Consumption, Building, Ginza, Real Estate, Economy, Lifestyle, Diagram

Louis Vuitton and Moët Hennessy merged in 1987, to create the world’s largest conglomerate specializing in luxury goods. In the years that followed, brands like Givenchy (1988), Céline (1996), and Marc Jacobs (1997) were acquired, indicating a big change in the global fashion industry.1 In the same period, Japan consolidated itself as a key player in the luxury market, at a time when property in Tokyo was relatively affordable post-bubble-burst. Kih Kotoyama pinpoints this moment with the acquisition of land, and consequent construction of flagship stores, by Hermès, Louis Vuitton, and Prada, at the turn of the millennium. The multi-billion yen investments these developments required, were recouped not by direct sales, but rather by the advertising potential of these buildings. They were effectively billboards, and the brightly lit facades were designed as such. “The building’s interior is of little concern,” Kotoyama writes, “because it’s recognition in the area as an icon is essential.”2

Similar tactics are now employed by fashion brands in countless shops around Ginza and Aoyama. None of these are bigger than Ginza Six: a 47,000m2 luxury shopping mall. A considerable part of the eighty-six billion yen investment was done by LVMH, and ten of the original tenants were Maisons from the group.3 Three of these – Fendi, Céline, and Dior – open themselves up to Chuo Dori Avenue, collectively forming a portfolio of sorts for the French conglomerate. Their facades, lampion-like structures that light up at night, are placed in front of the non-descript skeleton that forms the mall. The disconnect between exterior and interior, as brought forward by Kotoyama, returns in powerful fashion, and highlights the latest developments in the global fashion economy. Notably, Ginza Six is yet another iteration of Matsuzakaya, the historic department store that has changed the way the Japanese shop in this very location. It adapted a Western way of shopping early in the twentieth century, and became the very first store to allow shoes being worn everywhere inside.4

1. LVMH, “Milestones,” LVMH.com. Accessed March 8, 2020. https://www.lvmh.com/group/milestones-lvmh/1593-to-the-present/ 2. Koh Kitayama, Yoshiharu Tuskamoto, et al., Tokyo Metabolizing, (Tokyo: Toto, 2010), 15-17.

3. LVMH, “Ten LVMH Maisons open in Ginza Six retail complex in Tokyo,” LVMH.com, April 18, 2017. Accessed March 8, 2020. https://www.lvmh.com/news-documents/news/ten-lvmh-maisons-open-in-ginza-six-retail-complex-in-tokyo/

4. The Japan Times, “Matsuzakaya closes Ginza flagship for high-rise makeover,” The Japan Times, July 1, 2013. Accessed March 8, 2020. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2013/07/01/business/corporate-business/matsuzakaya-closes-ginza-flagship-for-high-rise-makeover/

See photos: Ginza Six